In a recent article published on its website, The Economist says the Nigerian economy has grown since acting president Yemi Osinbajo took over the mantle of leadership about a month ago.

In the article, the International business website called on PMB to leave the economy to Osinbajo to run once he recovers and comes back to Nigeria.

The full article below:

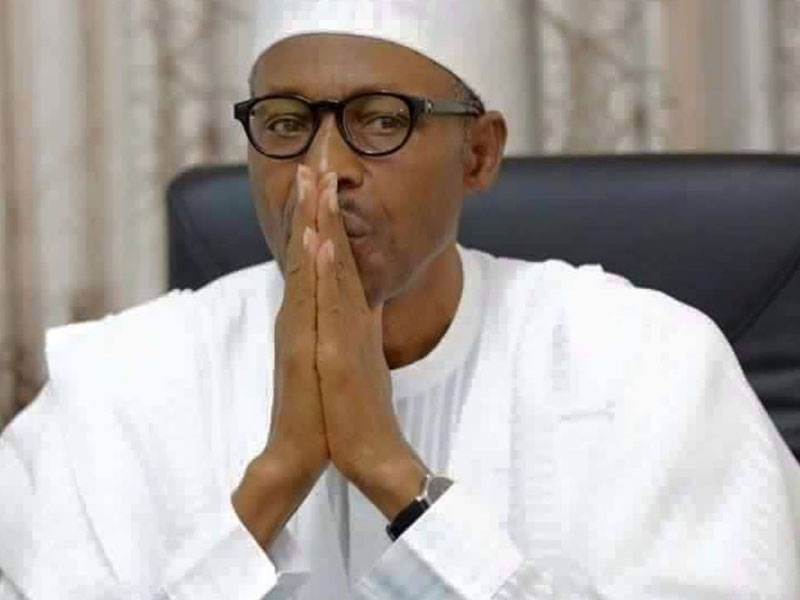

EVER since word trickled out that Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria’s 74-year-old president, was not just taking a holiday in Britain but seeking medical care, his country has been on edge. Nigerians have bad memories of this sort of thing. Mr Buhari’s predecessor bar one, Umaru Yar’Adua, died after a long illness in 2010, halfway through his first term.

During much of his presidency he was too ill to govern effectively, despite the insistence of his aides that he was fine. In his final months he was barely conscious and never seen in public—yet supposedly in charge. Since he had not formally handed over power to his deputy, Goodluck Jonathan, his incapacity provoked a constitutional crisis and left the country paralysed.

There is nothing to suggest that Mr Buhari is as ill as Yar’Adua was. But that is because there is little information of any kind. His vice-president, Yemi Osinbajo, insists that his boss is “hale and hearty”. Mr Buhari’s spokesman says his doctors have recommended a good rest. Yet even members of Mr Buhari’s cabinet have not heard from him for weeks, and say that they do not know what ails him or when he will return.

Such disclosure would be expected in any democracy. In Nigeria the need is even more pressing. Uncertainty is unsettling the fractious coalition of northern and southern politicians that put Mr Buhari into power. Nigeria is fragile: the split between northern Muslims and southern Christians is one of many that sometimes lead to violence. The country also faces a smouldering insurrection in the oil-rich Delta and an insurgency in the north-east by jihadists under the banner of Boko Haram (“Western education is sinful”).

Mr Buhari, an austere former general, won an election two years ago largely because he promised to restore security and fight corruption. Although his government moves at a glacial pace, earning him the nickname “Baba Go Slow”, he has wrested back control of the main towns in three states overrun by Boko Haram. Yet the jihadists still control much of the countryside, and the government has been slow to react to a looming famine that has left millions hungry.

On corruption, Mr Buhari has made some progress. A former national security adviser is on trial in Nigeria for graft, and a former oil minister was arrested in Britain for money laundering. So far, however, there have been no big convictions.

Mr Buhari’s main failures have been economic (see article). The damage caused by a fall in the price of oil, Nigeria’s main export, has been aggravated by mismanagement. For months Mr Buhari tried to maintain a peg to the dollar by banning whole categories of imports, from soap to cement, prompting the first full-year contraction of output in 25 years.

First, do no harm

With Mr Buhari in London, the country’s economic stewardship has, whisper it, improved a bit. Mr Osinbajo has allowed a modest devaluation and started on reforms aimed at boosting growth. This is already paying off. In February the government sold $1bn-worth of dollar-denominated bonds, its first foreign issue in four years. Demand was so great that investors bid for almost $8bn-worth of the notes, raising hopes of a second bond sale later this month. If his health recovers, Mr Buhari still has two years left in office.

He should focus on doing what he does best: providing the leadership his troops need to defeat Boko Haram and the moral authority to clamp down on corruption. And, noting how much better the economy is doing without him trying to command it like a squad of soldiers, he should make good on a long-forgotten electoral pledge to leave economic policy to the market-friendly Mr Osinbajo.